No. 10 (2014): Housing the Student

Housing for young people, specifically aimed at students, is an extremely hot topic at the moment. Due to the growing influx of (international) students to Dutch universities, student housing has again become a large-scale job, and the supply of quality housing is important in the battle for students. In a stagnant housing market, developers and investors alike are flocking to this job en masse.

Constant themes in the design of student housing are temporality, modularity and transformation. A new development is the conversion of vacant buildings, originally intended for other programmes, into housing for students. DASH 10 describes the history and typological variety of student housing, and maps out the needs of a new generation of city dwellers in order to take a look ahead – along with architects, developers, and policymakers – to see what is needed today and what will be needed in the future.

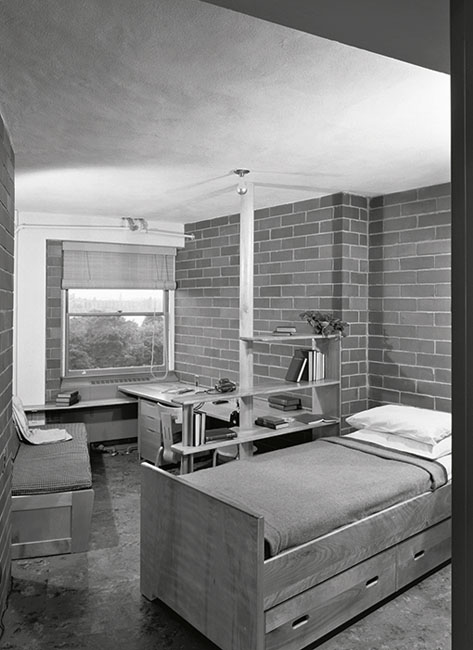

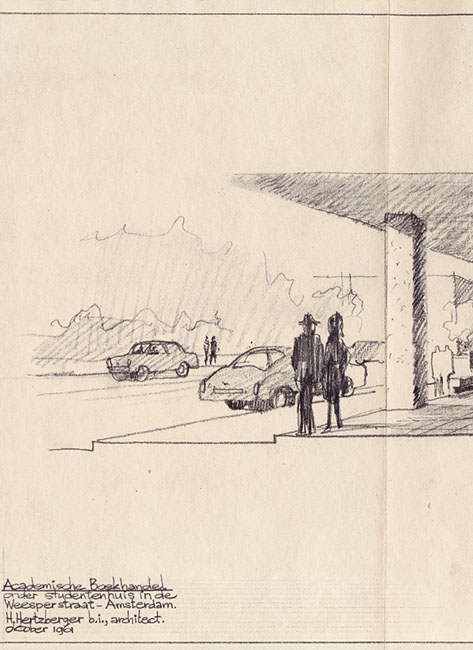

Dick van Gameren contrasts the English college model with the model of the North American campus from the perspective of the city, while Paul Kuitenbrouwer explores the typology of the student room in terms of its historical development and its many variations. Harald Mooij reconstructs the Dutch job of building student housing after the Second World War, and illustrates the then-lively debate with several early projects. In a fascinating history of Madrid’s Residencia de Estudiantes and its simultaneous occupancy by Federico García Lorca, Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel, Sergio Martín Blas shows that student housing can do more than merely provide shelter. Interviews with Niek Verdonk and Marlies Rohmer about topics including youth housing in Groningen, and with André Snippe, who is developing existing office buildings into Campus Diemen Zuid, link theory to current practice.

The plan documentation for projects including Eero Saarinen’s Morse and Stiles Colleges at New Haven; Cripps Building as an extension of St John’s College in Cambridge, by Powell & Moya; Maison d’Iran in Paris by Claude Parent & Heydar Ghiaï; the patio homes at Enschede’s Campus Drienerlo by Herman Haan; the small but special Svartlamoen project in Trondheim, by Geir Brendeland and Olav Kristoffersen; and the construction of a new building for Leiden University College in The Hague by Wiel Arets show the development of the student dwelling in all of its aspects, and on all scales.

Issue editors: Dick van Gameren, Paul Kuitenbrouwer, Harald Mooij

Editorial team: Frederique van Andel, Dirk van den Heuvel, Annenies Kraaij, Olv Klijn, Pierijn van der Putt

ISBN: 978-94-6208-122-2