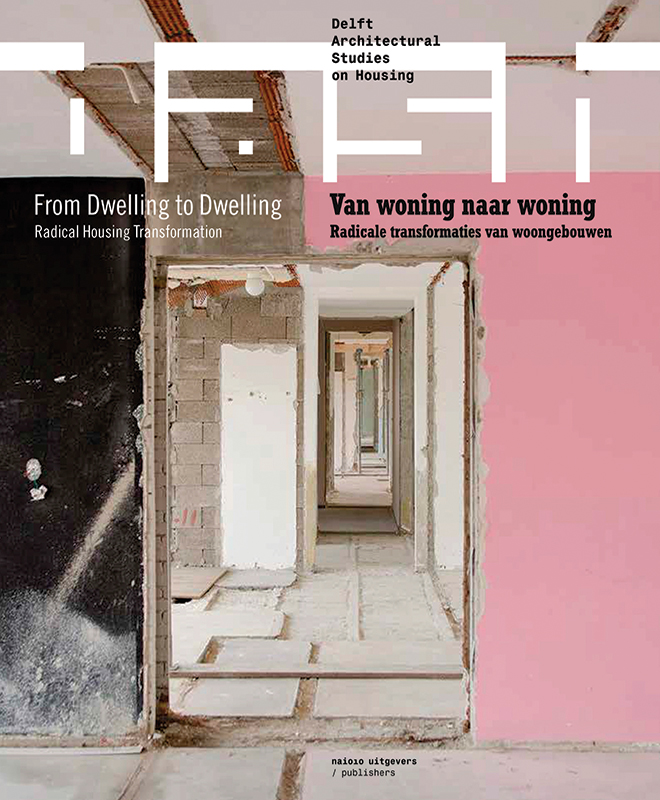

No. 14 (2018): From Dwelling to Dwelling: Radical Housing Transformations

A growing awareness of the necessity to use resources and social capital more sustainably has put the transformation of existing housing high on the agenda of developers and architects. The assignment is not just a technical one: changing dwelling habits mean that the space and configuration of the existing housing stock no longer meet current requirements, while from a sustainable, practical or cultural point of view, the buildings are worth keeping. This DASH puts the current objective in a historical and international perspective.

Issue editors: Dick van Gameren, Harald Mooij, Olv Klijn

Editorial team: Frederique van Andel, Dirk van den Heuvel, Annenies Kraaij, Paul Kuitenbrouwer, Hans Teerds, Jurjen Zeinstra

ISBN: 978-94-6208-311-0