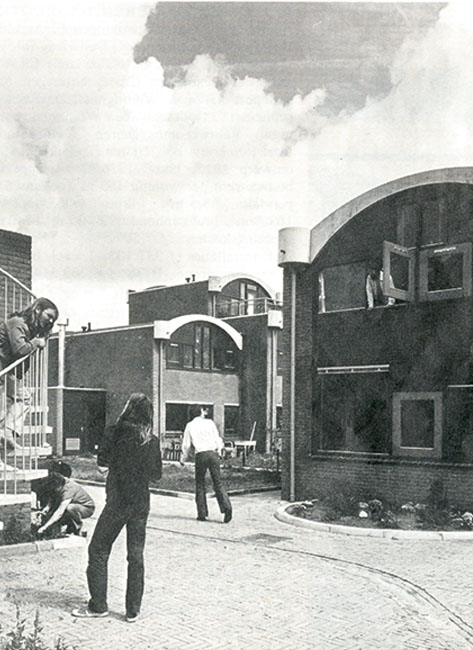

No. 08 (2013): Building Together: The Architecture of Collective Private Commissions

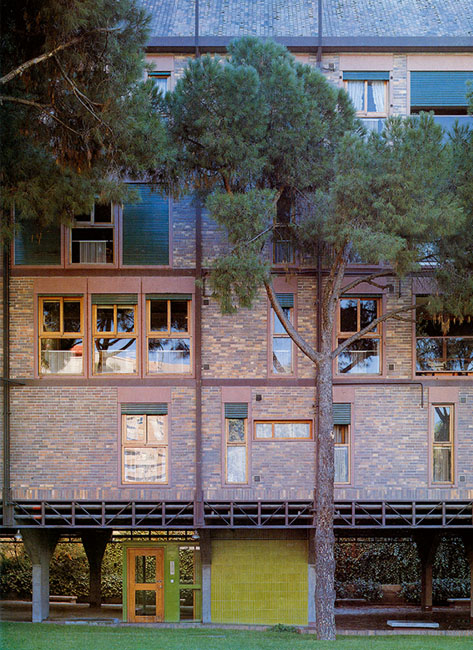

Several municipal governments in the Netherlands are looking closely at collective private building commissions. By stimulating private individuals to form commissioning collectives, cities like Almere and Amsterdam hope to relaunch the jammed housing market. In this they are taking a step towards what has been routine in Germany for many years under the name Baugruppen.

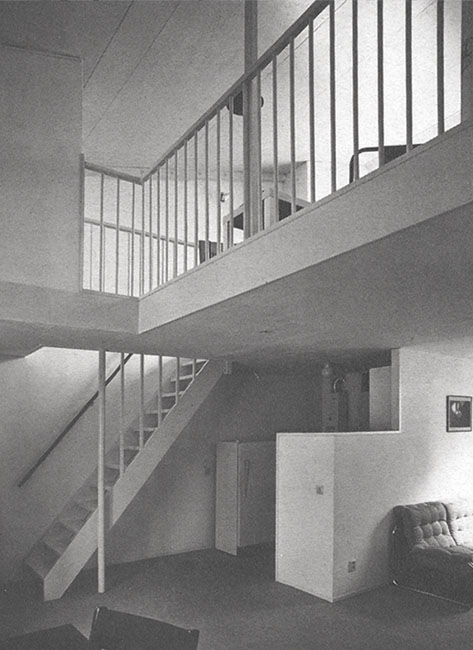

In the news coverage about Collective Private Commissioning (CPC), the economic and financial aspects usually take a central position. Often the opportunities that CPC offers for creating new forms of housing, programmes and floor plans that match the requirements of the user receive too little attention. It is precisely this side of the equation that DASH Building Together invests.

Through a number of essays and interviews, DASH shows that CPC collaborations in the Netherlands and abroad have resulted in innovative architecture for decades. With extensive plan documentation charts these programmatic and typological innovations in text and drawings, DASH Building Together provides an architectural slant on the collective private commissioning debate.

Issue editors: Dick van Gameren, Annenies Kraaij, Pierijn van der Putt

Editorial team: Frederique van Andel, Dirk van den Heuvel, Olv Klijn, Harald Mooij

ISBN: 978-94-6208-013-3