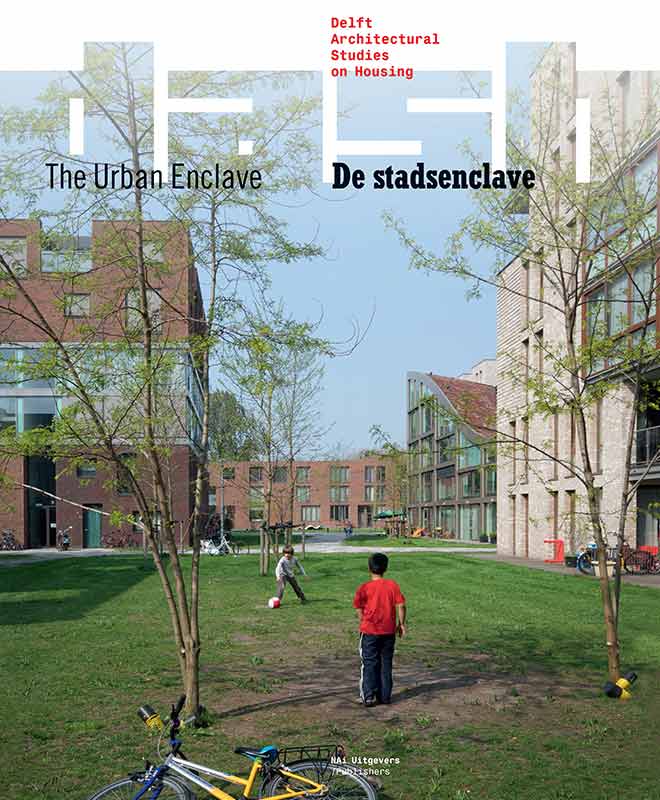

No. 05 (2011): The Urban Enclave

The idea of the pluriform city seems more current than ever. Society was still homogeneous 50 years ago; today highly divergent modes of life and culture are all seeking a place within our cities. This calls for a city with differences of its own, distinctive parts in which like-minded people can find one another, connected to the greater whole, but without imposing anything on others. The recent focus on regeneration within the existing city – especially on a mass scale – offers perspectives in this regard. In many cities in the Netherlands (and elsewhere) abandoned industrial and commercial premises or outmoded residential areas are being redeveloped. The usually sizable scale of these areas creates a (housing) construction challenge that can contribute to the needed differentiation within the city.

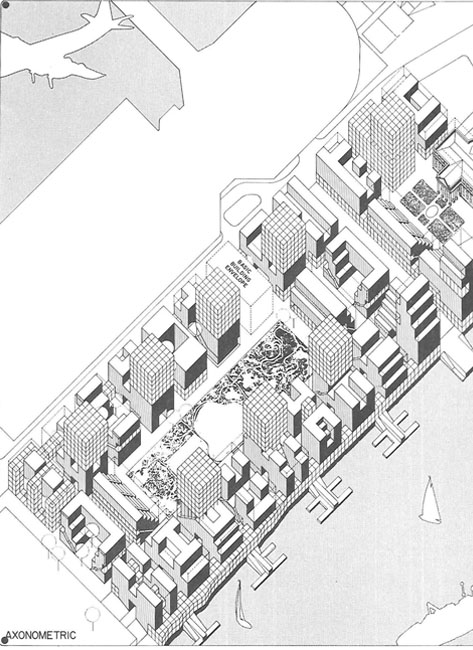

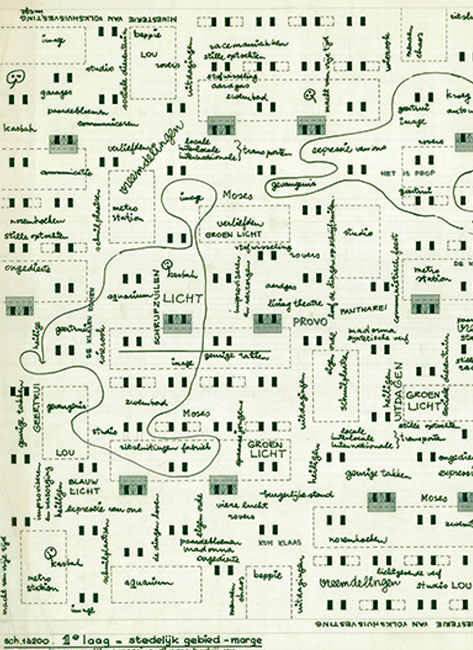

DASH 5 – The Urban Enclave is the product of an investigation into large-scale housing projects in the inner city, both historical and contemporary. Essays by Dirk van den Heuvel and Lara Schrijver examine divergent ideas related to large scales and the city, based on the work of Piet Blom and Oswald Matthias Ungers, respectively.

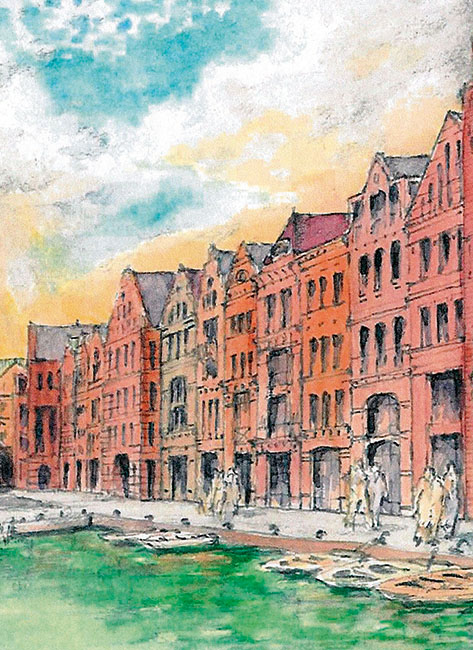

Dick van Gameren and Pierijn van der Putt look into the underlying typologies of the urban enclave. Elain Harwood analyses the evolution of the notorious Barbican in London, and Christopher Woodward charts the creation, in the same city 200 years previously, of the Adelphi, often cited as the inspiration for the Barbican. In an interview, architect and urban designer Rob Krier expounds on the historical models he uses for his urban renewal projects. The planning documentation contains a selection of urban enclaves old and new, extensively analyzed and documented with drawings and photographs.

Issue editors: Dick van Gameren, Annenies Kraaij, Pierijn van der Putt

Editorial team: Frederique van Andel, Dirk van Den Heuvel, Olv Klijn, Harald Mooij

ISBN: 978-90-5662-809-3