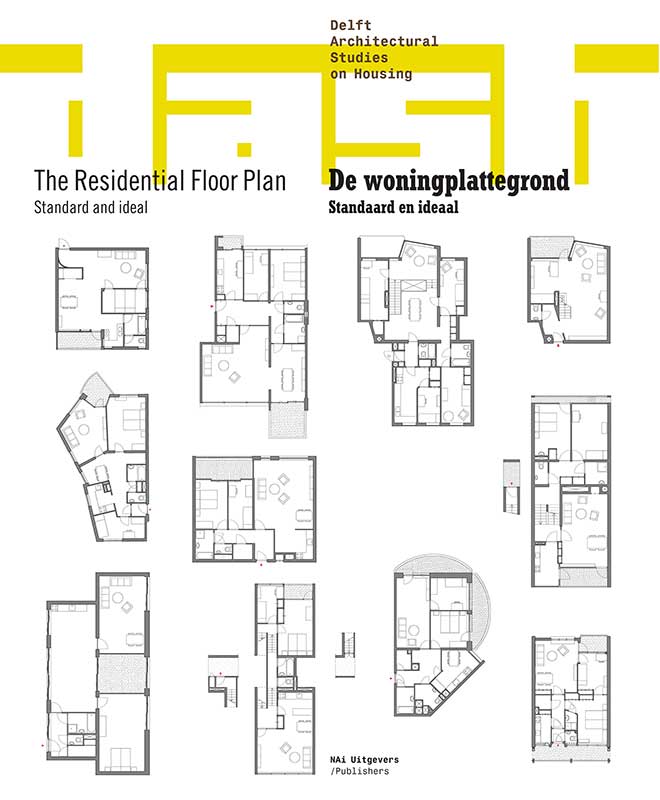

No. 04 (2011): The Residential Floor Plan: Standard and ideal

Although mass customization has for some time been the magic charm for banishing the specter of twentieth-century mass production, ‘standard’ solutions still prove the rule in everyday building practice. Strict regulations, conservative construction industry, and limited budgets have forced architects to obtain ideal designs by making the most of existing resources.

The Residential Floor Plan, Standard, and Ideal, the theme of DASH 4 (Delft Architectural Studies on Housing), addresses this dilemma facing architects of housing. It considers two approaches: on the one hand, the search for new typologies, familiar from modern architecture and the welfare state, and on the other typological invention, which takes existing house-building conventions as its starting point.

Essays by Dirk van den Heuvel, Dorine van Hoogstraten, and Bart Goldhoorn examine the scenographing of differences through typological recombinations in Dutch architecture in the late twentieth century, Habraken’s advocacy, in the 1960s, of viewing support and infill independently of each other, and the phenomenon of totally standardized, Soviet Russian mass housing, which offers points of departure for a reconsideration of standardization in a climate of free-market thinking. Interviews with Frits van Dongen and Edwin Oostmeijer provide insights into the issue of standardization from the perspective of architect and developer respectively.

The plan documentation comprises a series of classic and lesser-known projects from inside and outside the Netherlands, by architects such as Diener & Diener, Frits van Dongen, Dick Apon, Kenneth Frampton, Hans Scharoun, Van den Broek & Bakema, Willem van Tijen, Erik Sigfrid Persson, and Adolf Rading.

Issue editors: Dick van Gameren, Frederique van Andel, Olv Klijn

Editorial team: Dirk van den Heuvel, Harald Mooij, Pierijn van der Putt

ISBN: 978-90-5662-757-7