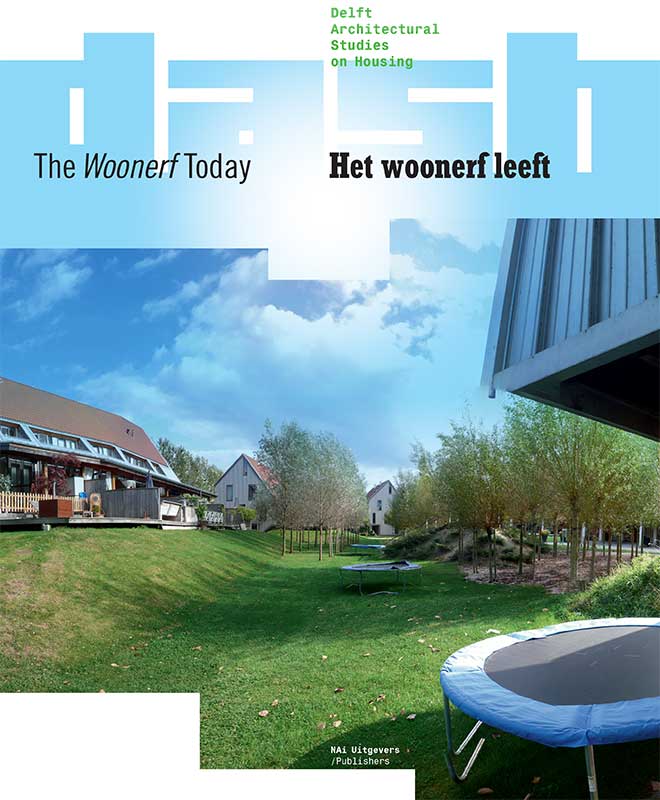

No. 03 (2010): The Woonerf Today

In ‘The Woonerf Today’, DASH (Delft Architectural Studies on Housing) examines the achievements of the Dutch woonerf, its background and current relevancy, and also considers the broader issue of living in a communal zone.

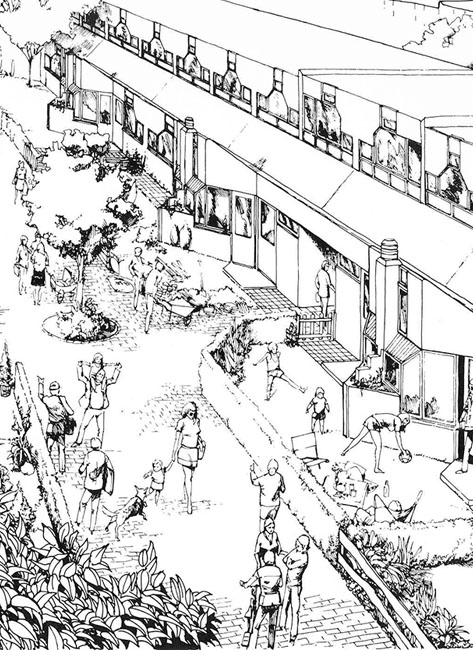

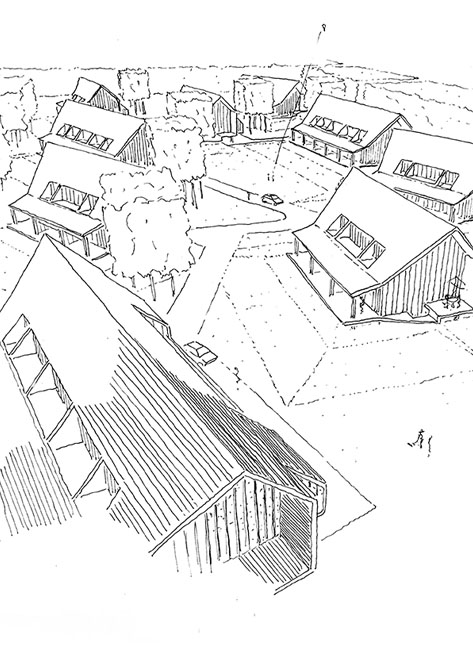

With its recognizable structures, informal interspaces, special traffic rules and wide application, the woonerf is one of the most distinctive concepts associated with residential design, deeply anchored in Dutch society since the 1960s and’70s. Its underlying principles, such as small-scale collectivity, green, ecological patterns and the connection between outdoor space , car and dwelling are still essential elements in building specifications today.

Outside of the Netherlands the Dutch woonerf is also recognized for its designation of pedestrian-priority, small-scale housing estates with informal architecture. A central topic in this third issue of DASH is the question whether the woonerf is still a useful concept to apply in small-scale, informal types of urbanization.

Essays and studies by Ivan Nio, Nynke Jutten and Willemijn Lofvers, Tom Avermaete and Eva Storgaard, Pierijn van der Putt, Dick van Gameren and Harald Mooij consider the spatial and social aspects of life in the communal space of a woonerf, providing detailed analyses of traditional examples and an exploration of current developments in Scandinavia and the Netherlands.

The documentation presents a wide range of inspiring solutions from the recent and less recent past, in the Netherlands and abroad, including projects by Vandkunsten, Onix, Stegeman, Zuiderhoek, Välikangas, Persson and Lyons.

Issue editors: Dick van Gameren, Annenies Kraaij, Harald Mooij

Editorial team: Frederique van Andel, Dirk van den Heuvel, Olv Klijn, Pierijn van der Putt

ISBN: 978-90-5662-793-3