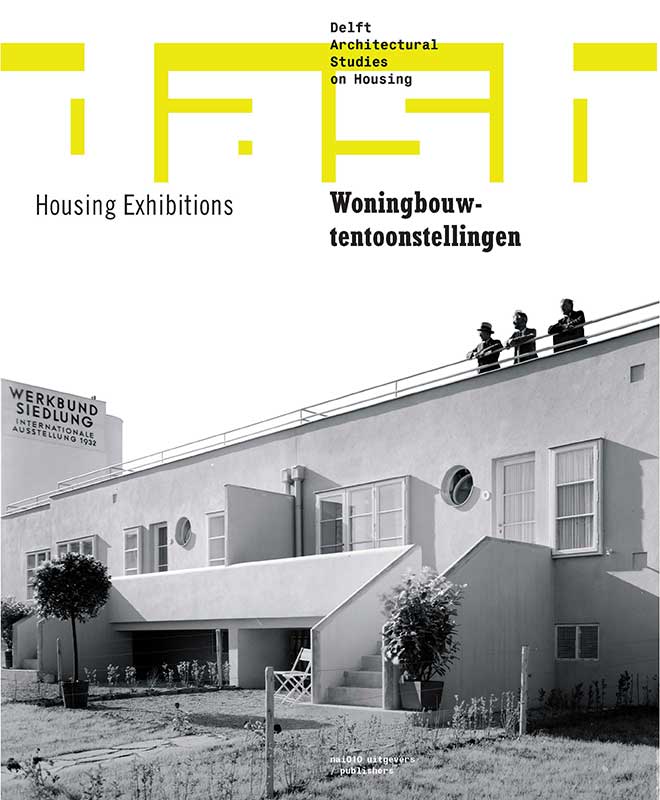

No. 09 (2013): Housing exhibitions

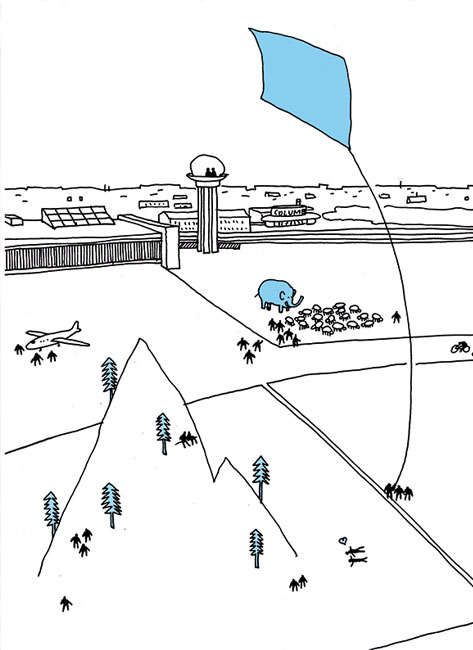

Housing exhibitions in which the houses themselves are displayed as built objects (either temporary or permanent ones) had a major influence on the development of the twentieth century’s residential architecture. These exhibitions were underpinned by often-changing objectives, such as the uniting of architecture, art and industry, or the demonstration of new construction techniques. Issues such as the shortage of housing formed an important part of the programming in the 1930s, and also during the post-war reconstruction period. Cloaked ambitions such as the promotion of architectural ideals and the expression of political views can often be properly traced after the fact. These days, building exhibitions are rarely limited to housing alone; themes such as sustainability and climate change are also high on the agenda. Since the 1980s, and mainly in Germany, attention has been drawn to entire cities and regions via an Internationale Bauausstellung (IBA), without any fixed planning concept, but rather as the initiator of an open-ended transformation.

DASH 9 focuses on the objectives, results, and consequences of housing exhibitions. Essays by Frederique van Andel, Lucy Creagh, Sandra Wagner-Conzelmann, and Noud de Vreeze make connections between various exhibitions and major milestones in the history of residential architecture.

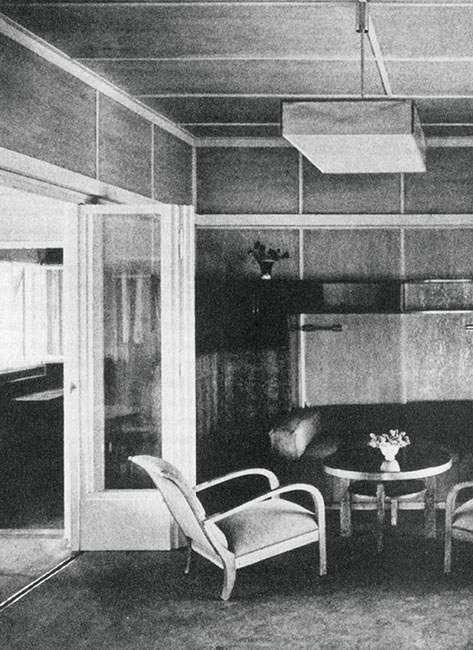

The planning documentation includes a series of well-known and less well-known exhibitions, such as ‘Ein Dokument Deutscher Kunst’ in Darmstadt, ‘Die Wohnung unserer Zeit’ in Berlin, the Werkbund Exhibition in Vienna, ‘Il Quartiere Triennale 8’ in Milan, and the ‘Documenta Urbana’ in Kassel. More recent exhibitions that are explored include the ‘City of Tomorrow’ in Malmö and the IBA in Hamburg, which ended in 2013.

An interview with Barry Bergdoll examines the tradition of homes being exhibited on a 1:1 scale in the Museum of Modern Art’s sculpture garden in New York. DASH also discusses with Vanessa Miriam Carlow, a member of the ‘Prae-IBA-Team’, whether the ideas for the canceled IBA 2020 in Berlin might still be of value for that city.

Issue editors: Dick van Gameren, Frederique van Andel

Editorial team: Dirk van den Heuvel, Annenies Kraaij, Olv Klijn, Harald Mooij, Pierijn van der Putt

ISBN: 978-94-6208-098-0