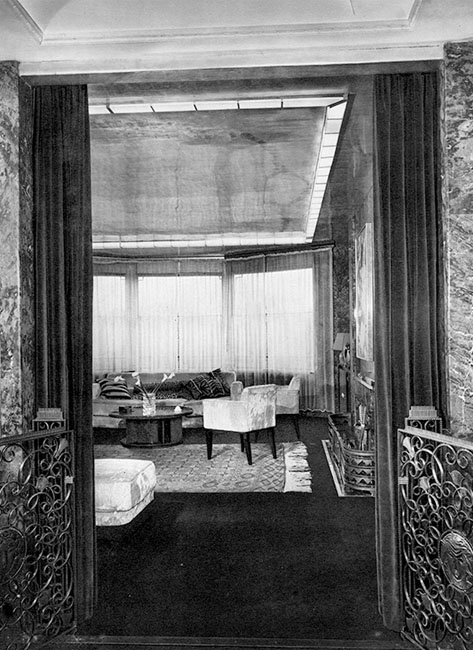

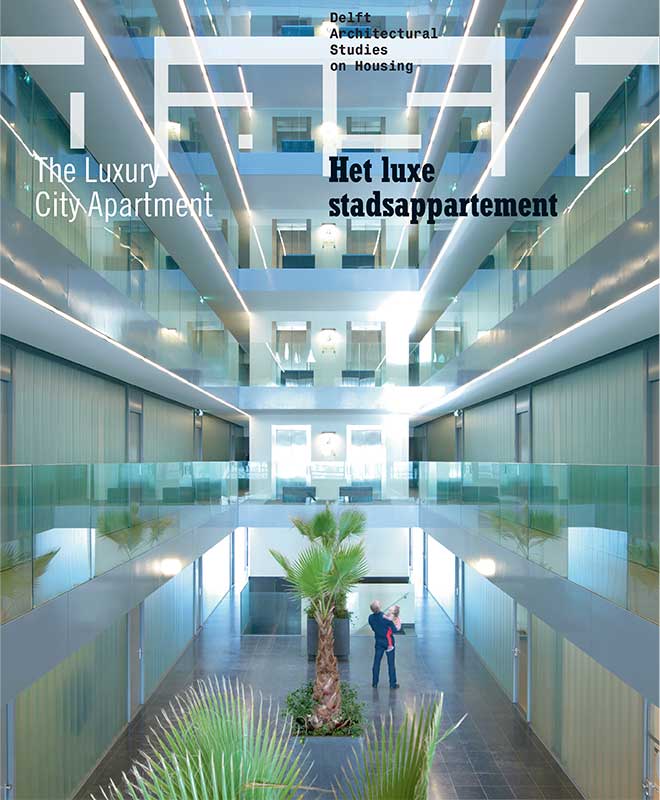

No. 02 (2009): The Luxury City Apartment

The second issue of DASH focuses on the emergence of the luxury city apartment. The articles range from historical explorations of luxurious apartments built in Paris and London in the late 19th century and the full-service apartments realized in The Hague in the early 20th century to the emergence of enclaves for the wealthy in Brazil. There is also an article comparing the Dutch market with the market in Berlin and an account of the turbulent history of a luxury apartment complex in the Netherlands. The power of the market and the role of developers is investigated in a discussion with Huub Smeets, CEO of Vesteda residential property developers, while the architect Winka Dubbeldam sheds light on the situation in New York. The projects discussed, including several recent examples in the Netherlands, are documented in detail. The residential layouts, the collective spaces (entrance foyers) and the services and amenities in the luxury appartments are subject to specific requirements. What does this imply for the building and for the relationship between the building and the surrounding city? With contributions by Monique Eleb, Dick van Gameren & Christoph Grafe, Vincent Kompier and Paul Meurs, among others Including projects by Herzog & de Meuron, awg architecten, Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza and Auguste Perret.

Issue editors: Dick van Gameren, Sebastiaan Kaal, Pierijn van der Putt, Paul Kuitenbrouwer

Editorial team: Frederique van Andel, Dirk van den Heuvel, Olv Klijn, Harald Mooij

ISBN: 978-90-5662-717-1