Editorial

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.7480/dash.07.4709Abstract

Forty years after the first oil crisis and the Club of Rome’s controversial report Limits to Growth, environmental awareness and sustainability are starting to become an integral part of construction practice. The new shortages of energy and raw materials precipitated by the rise of new economic superpowers like China are partly responsible. In addition, the United Nations climate conferences and Al Gore’s film An Inconvenient Truth have helped make the public at large aware of the negative repercussions of our way of life.

Construction is responsible for about 20 per cent of total carbon dioxide emissions and 30 per cent of energy demand; this ranks it alongside the chemical and transport industries among the biggest polluters. Sustainability is therefore one of the most significant issues for designers and architects, as well as a challenging field for innovation and research. Yet simple solutions are not easily available. A wide range of approaches are now being demonstrated in practice, from the idealistic-holistic and politically engaged to the pragmatic and commercial. At times these approaches complement each other; at times they frankly conflict.

Take for instance the much-discussed Cradle-to-Cradle philosophy of American architect William McDonough and German chemist Michael Braungart. Energy supplies, remarkably enough, are not an issue within Cradle-to- Cradle thinking as long as this energy is generated sustainably and the cycle of material flows are well organized without exhausting natural sources. Superuse, the name given by the 2012Architecten bureau to its approach to material recycling in architecture, is paradoxically at odds with the Cradle-to-Cradle concept. From McDonough and Braungart’s perspective, such an inventive form of recycling begins at the wrong end of the system and Superuse is nothing more than a further degradation of materials in the various cycles of reuse. There are many other conflicting approaches: in counterpoint to Danish architect Bjarke Ingels of BIG, who advocates a new hedonistic architecture that, free of Protestant guilt, exploits the opportunities of reuse and energy management to the utmost, we find the international movements of eco-village and Transition Towns, which propagate new definitions of social responsibility through alternative lifestyles and forms of good governance.

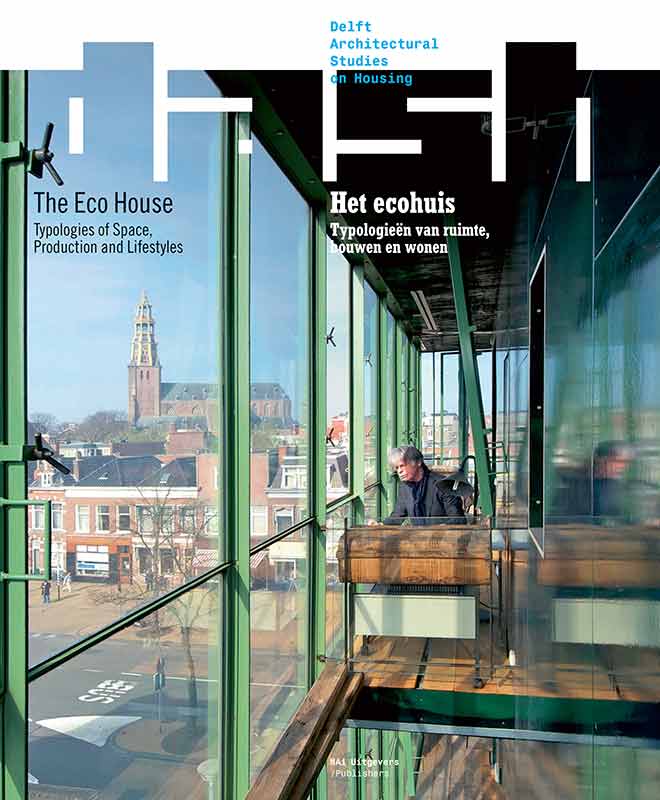

In order to demonstrate the various basic principles and possibilities of a sustainable architecture of housing, this issue of DASH is devoted to the eco house. As architectural design is the focus, the discussion primarily concentrates on architectural invention rather than on the application and integration of today’s highly advanced (and often expensive) technological remedies, such as climate-control installations. The house by Carlos Weeber in Curaçao is one of the most evident demonstrations – a comfortably interior climate is achieved without the use of air conditioning, but through principles of cross-ventilation, shade and natural cooling. The organization of the interior climate by dividing the home into zones produces special typologies that are characteristic of the eco house, from the hippie architecture of Earthship and Dome to cosy, middle-class conservatories in the back garden.